The Overton Hoard: A Severan Hoard from North Yorkshire – By Emily Tilley, Curatorial Assistant, Roman Archaeology

In 2016 a hoard of 37 Roman silver denarii and fragments of a drinking vessel was found in Overton, a village just outside York.

The discovery was reported to the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and declared Treasure. It is recorded on the PAS Database as YORYM-BE3F22.

The Overton Hoard was acquired by York Museums Trust in early 2018 and first went on public display at the Yorkshire Museum in October 2018.

The Overton Hoard coins. ©British Museum. Object number YORYM : 2018.154.

The hoard was deposited during the reign of the emperor Septimius Severus, with the latest and least worn of the coins dating to AD 193-211. The earliest coins in the hoard are much older, dating to the reign of the emperor Vespasian in AD 69-79.

One of the latest coins in the hoard.

Septimius Severus, issued AD 193-211. Reverse depicts a winged Victory holding a wreath and a palm branch. ©British Museum. Object number YORYM : 2018.154.39.

At first glance this date range might seem unusual, but denarius coinage was in use (in varying forms) from c.211 BC to the mid-3rd century AD.

In the years leading up to the deposition of the Overton Hoard, the amount of silver in the denarius had been greatly reduced while its face value remained the same. This process is called debasement.

The higher quantity of silver in older denarii, like the earliest denarii in the Overton Hoard, meant that they stayed in circulation for a very long time. They would still have been in everyday use when this hoard was hidden, 150 years after they were first issued, and their highly worn condition indicates that they were passed from person to person extensively before they were placed in the ground.

It is possible that whoever buried this hoard intentionally included the older denarii, knowing that their precious metal value was higher than the newly minted coins.

The earliest coin in the hoard.

Domitian, as Caesar, issued under Vespasian, AD 69-79. Reverse depicts Spes holding a flower. ©British Museum. Object number YORYM : 2018.154.3.

The hoard was deposited at a significant moment in York’s Roman history. In AD 208 the emperor Septimius Severus travelled to York with his wife, Julia Domna, his sons, Caracalla and Geta, and an army of approximately 30,000 men. Scottish tribes who lived north of Hadrian’s Wall had been attacking Romano-British settlements in the north of Britannia, and the emperor used the Roman military fortress and city of Eboracum (York) as the base for his military campaigns against them.

The imperial family and court was based in York until Septimius Severus’ death in AD 211. On his deathbed, according to Roman historian Cassius Dio, Severus said “When I took over the state chaos reigned everywhere; I am leaving it at peace, even Britain…the empire which I am leaving my sons is a strong one…”.

His body was cremated on the outskirts of York and his remains were returned to Rome. His sons soon negotiated a peace treaty with the Scottish tribes.

Caracalla awarded Eboracum the status of a Colonia, the highest status a Roman city could hold, and it became the provincial capital of Britannia Inferior, northern Britain.

The presence of the imperial family, court, and additional military forces had a dramatic cultural impact in Roman York.

Septimius Severus was from Leptis Magna, in modern day Libya, and his wife Julia Domna was from Emesa in Syria. They brought Eastern fashions, religious practices, and goods to York, and this is strongly reflected in the city’s archaeology.

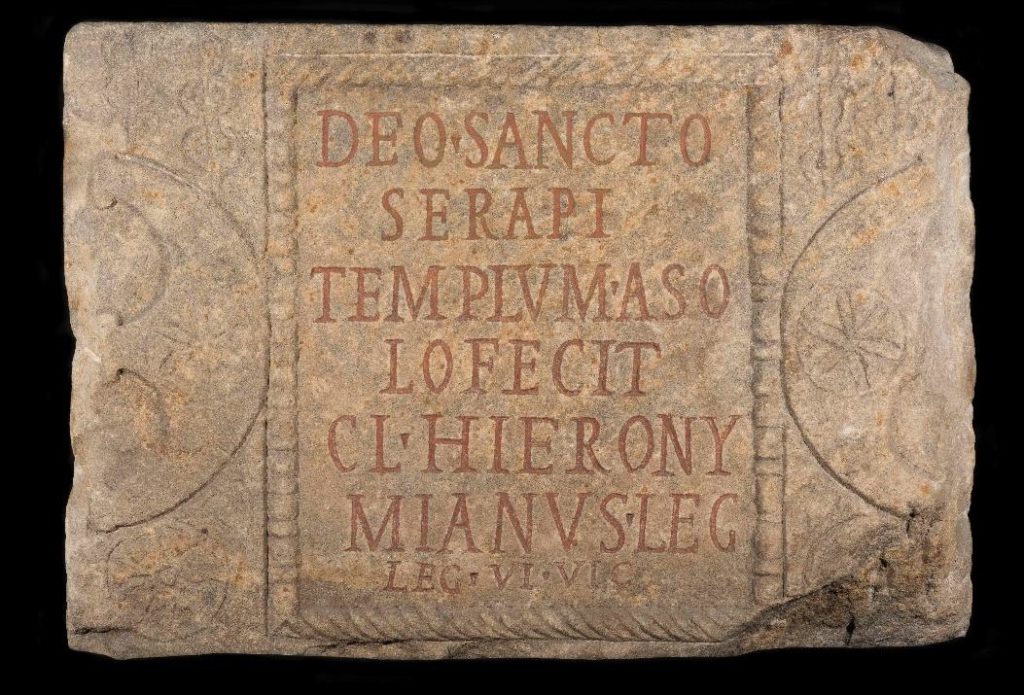

For example, a temple in York was dedicated to the Egyptian god Serapis and African style head pots began to be used in the city. Life in York changed dramatically.

Dedication to the Temple of Serapis, c.AD 190-212. ©York Museums Trust. Object number YORYM : 1998.27.

Head pot depicting Julia Domna, c.AD 200-300. ©York Museums Trust. Object number YORYM : H2132.

There must have been a similarly significant impact on Roman York’s economy, but this is more difficult to trace.

The practice of hoarding in Britain became more common between AD 193 and AD 196, around the time of the Scottish attacks on northern settlements. This became less common in c.AD 197, just after Septimius Severus reportedly sent a new governor, Virius Lupus, to Britain to pay the Scottish tribes to cease their attacks.

This trend is possibly an indication of economic uncertainty in the years preceding Septimius Severus’ arrival in York, and might suggest that imperial action to subdue the tribes had some success in restoring confidence among the people of Roman Britain.

Cassius Dio records that Septimius Severus brought huge quantities of supplies, probably including wealth and coinage, to Britain. Certainly much money would have been needed to pay the 30,000 soldiers who accompanied him on his campaign. This will have caused a huge increase in the amount of coinage in circulation in Eboracum and Roman Britain as a whole.

A large number of hoards dating to the Severan period have been found in Britain, including several from around York. The Overton Hoard is the Yorkshire Museum’s only example, and as such provides valuable insight into how life in Roman York was impacted by the events surrounding the Severan imperial presence in the city.

If you’ve enjoyed this blog, why not come along to our Coins of the Roman Republic Curator’s Talk at the Yorkshire Museum? Find out more.

Bibliography:

Moorhead, S. (2013). A History of Roman Coinage in Britain: Illustrated by finds recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme. Greenlight Publishing, pp.105-107.

Bland, R. (2018). Coin Hoards and Hoarding in Roman Britain AD 43-c.498. Spink, pp.56-59.