Pushing the Great Auks into Extinction – By Kate Whiteway

This blog post was written and researched by Kate Whiteway, a Science Communication (Msc) student from the University of Sheffield who is currently undertaking a placement with us here at the Yorkshire Museum.

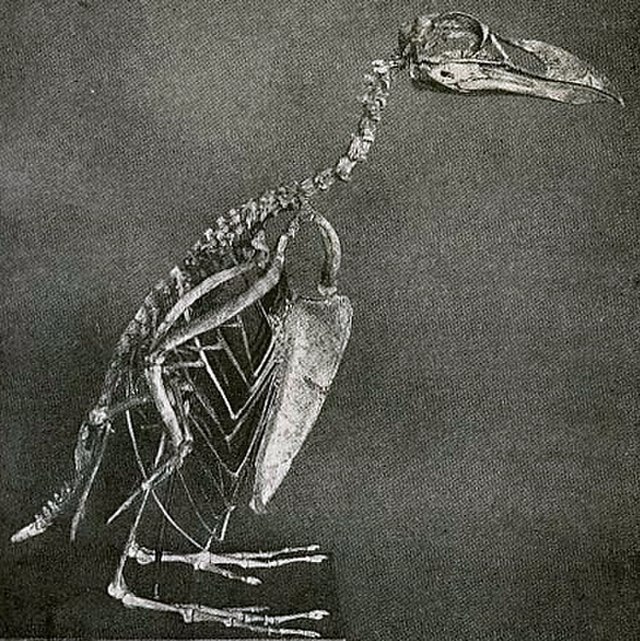

Two Great Auks sit in the archives here at The Yorkshire Museum. These specimens and those like them are the only remaining evidence of colonies thousands strong, across the coasts of the northern hemisphere.

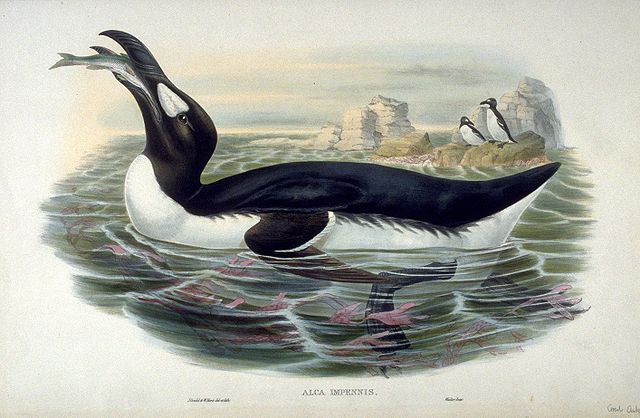

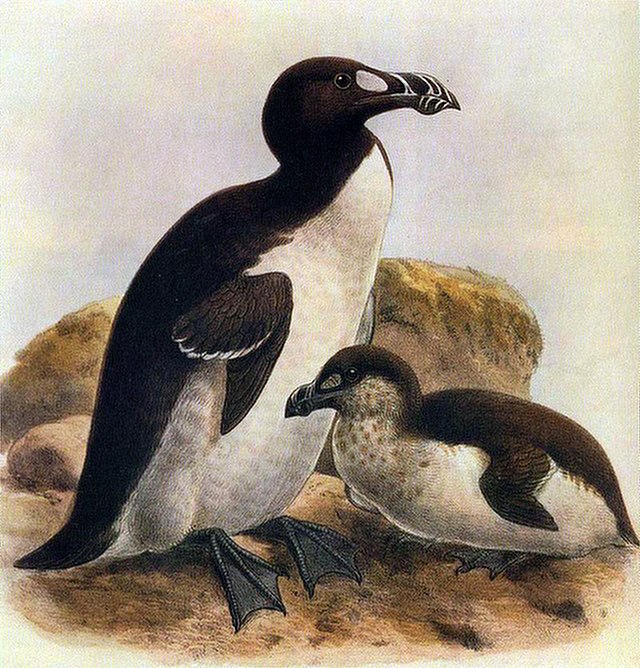

These birds, nicknamed the original penguins because of their penguin-like appearance, were roughly 75 cm tall with black and white feathers. They had slender, curved beaks for hunting crabs and fish. They lived between the land and the sea, emerging from the water only to breed. That is until they encountered people.

Garefowls as they were also known were adept in the water. Swift and talented swimmers. Much of what we don’t know about them is due to their disappearance into the sea over the winter, where they were out of reach. An account of a free-swimming garefowl by William Bullock Recounted by George Montague explains “so expert was the bird in its natural element, that it appeared impossible to shoot him. The rapidity with which he pursued his course underwater was almost incredible”.

These adaptations however, made them unfortunately inept out of the water. Their feet, being too far back on their bodies, were unsuited to travelling on land. Waddling and flightless, they were vulnerable.

On a trip to St Kilda, two fishermen came across a bird that they then captured. They kept it in a small shelter on the island where they could watch as it stared with its bill agape, occasionally snapping it violently. However, when the island was hit by a strong storm, they started to believe that the bird was a witch that had brought on this heavy weather. The fishermen Cruelly killed the bird. One of many incidences of violence against the Great Auks.

Auks had many uses to people. Having exhausted the eider feathers, auk feathers were used as down, to fill pillows, duvets, and mattresses. Funk Island was a particularly brutal extinction.

There the birds were plucked, cooked, and used to fuel fires in their thousands. The ease of capturing them drew more people to seek them out and their numbers began to fall.

Once the auks started to decline, people did take notice. Scientists and collectors clambered to get their own Great Auk specimen before they went extinct. They would pay high sums for a Great Auk, which inevitably led them further into decline.

Then on the 3rd of June 1844, a couple of fishermen came ashore at the Icelandic Island of Eldey. They spotted a single pair of great Auks and scrambled to capture and kill them. Only once the ordeal was over did they realise that the pair had been incubating an egg. An egg that was now crushed, in the rush underfoot; and the Great Auks were extinct. Although we can never be certain that these were the very last pair, this is the final story that we can tell.

Our specimens, one of which is thought to be a St Kilda bird, are two of perhaps 70 mounted specimens that exist in the world. The last remnants of the great auks. Richard Whitbourne described the Great Auks in 1622 as “Such an admirable instrument for the sustenation of man”, now they fall into legend, their value lies in their extinction. If only we might have valued them when they were alive.

(All images used are in the public domain).