Prisoner Stories: Mary Bateman

Content advice

This blog post contains information that could be upsetting, including discussion of murder and execution. It talks about crimes and a punishment that were carried out over 200 years ago.

Working in the stores at York Castle Museum, I often come across little mysteries. This broadsheet is one of them. It tells the stories of people who were executed at the Drop (gallows) at York Castle on 20 March 1809, and was printed to be sold to the crowd on the day of the execution. It features a woman called Mary Bateman, but one of the details doesn’t add up. The broadsheet tells us that:

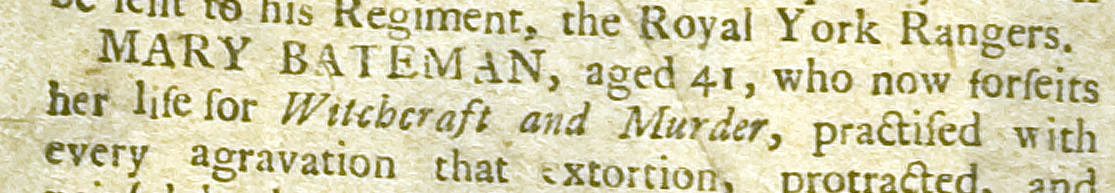

‘Mary Bateman, aged 41, […] now forfeits her life for Witchcraft and Murder’

That can’t be right. English law used to allow courts to convict and execute people for witchcraft, but those laws had been repealed in 1736 – nearly eighty years before Mary’s trial.

We learn from other sources that Mary wasn’t convicted for witchcraft at all – she was executed for the murder of a woman called Rebecca Perigo. But we also learn that Mary had claimed to have uncanny powers. She had sold her services as a wise woman – telling fortunes, making charms and performing other spiritual or supernatural tasks in exchange for money.

So why did the broadsheet mention witchcraft if that wasn’t correct? Although the legal system no longer recognised accusations of witchcraft as valid, the idea of the witch was very strong in people’s imaginations. The broadsheet uses the word to grab and hold its readers’ attention. Broadsheets were more about gossip and entertainment than news; they tended to be sensationalist and were known to embellish the facts to make a better story.

All this leaves us with a new set of questions: Who was Mary Bateman? And what really happened?

We can piece the story together from newspaper reports and other sources published around the time of her execution, and from surviving court records. Like with the broadsheet, we have to be careful when we use these sources – we need to remember that no source is guaranteed to be truthful or accurate. We also don’t have any sources that tell us in her own words what Rebecca Perigo thought about her interactions with Mary Bateman in the months before her death.

Mary’s early life was ordinary. She was born Mary Harker in 1768, to a small-scale farming family at Aisenby, near Thirsk (a town north of York). Like many girls of her social class, she learnt to read and write, and she was raised for a life of domestic labour and farm work.

In 1780, when she was around 12 or 13 years old, she took a job as a domestic servant in Thirsk. This was normal for girls of Mary’s background, who would expect to take a job in service until they were ready to get married and start a family. But unlike most children, Mary had already begun to steal. Her first job didn’t last long, and she went through several employers in her teenage years. When she was 15, she settled in Leeds and took a job as a veil or mantua maker. Making clothes was very poorly paid, and Mary developed a sideline in fortune telling.

In 1792, when she was 24, Mary married a wheelwright called John Bateman. After her marriage, she began stealing on a bigger scale. Records tell us she stole from people who lived in the same lodging houses where she and her husband rented rooms. She also committed fraud – she made purchases from Leeds shops in the name of established customers, and went door-to-door begging linen and clothing for the sick and the poor. She would then pawn or sell the items for her own profit.

The surviving records strongly hint that her husband initially had no idea about her secretive life of crime. But one day, he came home to find out that Mary had sold all their furniture to pay off one of her victims.

John Bateman soon joined the army. It has been suggested that he did this to get Mary away from Leeds, and that he hoped to break her cycle of stealing to compensate for her previous thefts.

In 1799 they returned to Leeds, and Mary began to grow her reputation as a wise woman. Wise or cunning folk were people who sold a range of services. These included helping people find lost property, curing ailments in humans and animals, and influencing the weather. English cunning folk were not witches, and they weren’t pagan; they used Christian prayer alongside charms and spells.

Like traditional wise folk, Mary made potions and charms as well as telling fortunes. It isn’t clear whether Mary herself believed that she had uncanny powers, but she knew she could make money from it.

In 1805, Mary had a hen which she claimed was prophesying the end of the world. It laid eggs inscribed ‘Christ is coming’. For a penny, people could visit the hen. We don’t know how Mary convinced people the hen was actually laying these eggs, but eventually it was moved to a new home, and it only lay regular eggs after that.

Mary didn’t just rely on her own reputation. She acted as an intermediary for fictional wise women who lived far enough away that her customers couldn’t easily check whether they were real. These imaginary women, Mrs Moore and Mrs or Miss Blyth, both required communication by post. Mary was in charge of posting the letters. She charged postage fees with every letter she pretended to send, but kept the money along with her own fees.

Also, Mary was an attender at meetings for Joanna Southcott, a Christian millenarian prophet – that is, a person who was prophesying the imminent end of the world. Mary began to use Joanna’s name to add authenticity to her own work, and there’s no evidence she asked permission.

In 1806, Mary set out on the path that would eventually lead her to the gallows. She began to treat Rebecca Perigo of Bramley, near Leeds. Rebecca was in her mid-40s and was convinced that she had a nervous or spiritual ailment. Her husband William seems to have been desperate to find her a cure. Rebecca’s niece suggested they get in touch with Mary, which shows how successful Mary was at developing her reputation.

In the course of ten months, Mary extracted £70 in money (this is more than a skilled tradesman would earn in a year), clothing, furniture and other household goods from Rebecca and William Perigo. Some of the money was meant to be made into charms and sewn into Rebecca’s mattress. Some of it was meant to go to the fictional wise woman, Miss Blyth. Mary took money for postage, as she had from other people in the past. The letters which claimed to be from Miss Blyth contained instructions about what goods the Perigos should give to Mary for her – but as Miss Blyth didn’t exist, Mary would keep those. The letters also told Rebecca and William to destroy all correspondence afterwards.

In May 1807 she told the Perigos they were about to fall sick from an illness that God had in store for them. To preserve them from this illness they had to follow Miss Blyth’s instructions. If they didn’t follow the instructions perfectly, death was certain.

Mary began to send them a series of white powders, with instructions to mix them into a pudding and eat it all. She guaranteed this would save them. They couldn’t let anyone else eat any of the pudding, not even animals. They had to destroy any that was left over, and they weren’t allowed to consult with a doctor, as Mary told them the doctor could not help them.

The first few powders seem to have been harmless, but the sixth powder was lethal. Rebecca ate all of her pudding, while William could only manage a spoonful of his. They were both violently ill for 24 hours, but they obeyed Miss Blyth and didn’t call a doctor. Instead, they took a honey mixture provided by Mary which she promised would offset any side effects of the ‘magical’ powder.

On Sunday 24 May 1807, a week after eating the pudding, Rebecca died. Reports at the time told that her tongue was badly swollen and her features discoloured and distorted.

Despite Rebecca’s death, William didn’t go to the authorities. He kept on consulting with Mary, asking her about the failure of previous spells, and the cause of his wife’s death. He sent more things to the fictional Miss Blythe, including his late wife’s dresses. In one letter Miss Blythe complained that he had sent her a shabby dress, when she needed one fit for evening wear.

Eventually William became so desperate for money that he opened the charms sewn into the mattress. These should have contained gold and guineas given to Mary. Inside were pennies, farthings and scrap paper.

On 20 October 1808 William finally went to the authorities. They found various substances on Mary, including a white powder that turned out to be a corrosive form of mercury, which had been mixed into honey.

Mary claimed William had given her the pot the night before her arrest, in an attempt to entrap her. The authorities did not believe her.

She was taken to York Castle, where she was charged with the wilful murder of Rebecca Perigo.

While in prison, Mary continued to serve as a cunning woman. She met a young woman prisoner who wanted to see her sweetheart. Mary told her that if she could get a sum of money, Mary would sew it into a charm to wear inside her stays. This, she said, would make the young man visit her. The young woman found the money, but the young man made no appearance, and the lass opened the charm to find her money had mysteriously vanished. The Governor of the prison got involved, and made Mary refund the sum she hadn’t already spent. The balance was paid by Mary’s friends.

Mary was imprisoned in what was, at the time, the newest of York Castle’s buildings. We don’t know exactly where her cell was, but we know she would have walked in the exercise yard that is now Kirkgate, the museum’s Victorian Street, and she would have come to the chapel for Christian worship.

While in prison, Mary wasn’t alone. We know from reports at the time that she was breastfeeding her youngest child, and the child stayed with her. It was usual for nursing infants to be kept in prison with their mothers.

In the early nineteenth century, the court didn’t hear trials all year around. Instead, it met at certain times of the year, and prisoners awaiting trial had to wait until the next meeting for their case to be heard. This is why Mary was arrested in October 1808, but her case didn’t come to trial until March 1809.

The trial was held in the Assize Court building, now the Crown Court, opposite the prison. It lasted 11 hours, and the jury only needed minutes to pronounce her guilty. She immediately declared she was 22 weeks pregnant. Pregnant women could ‘plead the belly’, which often led to a stay of execution and could lead to their sentences being reduced afterwards.

As Mary was breastfeeding during her time in prison, it was unlikely that she was pregnant, but the judge had to take her claim seriously. He ordered a panel of matrons (married women) to be drawn from the women present – this was standard practice, as it was thought that married women who had given birth had the experience to assess whether another woman was pregnant. The women were ordered to inspect Mary’s body and see whether she was telling the truth. They concluded that she was not pregnant, and the judge sentenced her to be hanged.

Mary Bateman was hanged at the gallows overlooking St George’s Fields on 20 March 1809, three days after her trial. The day before her execution, she wrote to her family and admitted instances of fraud, but she went to her death denying her guilt at Rebecca Perigo’s murder.

In the early nineteenth century, the bodies of executed criminals were routinely given to medical science. That crowd of 5000 people who came to witness Mary being hanged were joined by many people who lined the road from York to Leeds to watch her coffin on its journey from York Castle to Leeds General Infirmary. Her body was given to the surgeons for dissection. Hospital staff charged visitors 3d each to view her corpse. They made £30 from it, meaning 2700 people came to view her. A large portion of her skeleton was on display at the Thackray Medical Museum in Leeds until relatively recently.

What do you think about the case of Mary Batemen? Come talk to us on Facebook or Twitter if there’s something you’d like to know about the lives of people at York Castle

You can listen to an audio recording of this blog below.