PICTURES OF THE FLOATING WORLD: DISPLAYING YORK ART GALLERY’S JAPANESE PRINTS (BLOG 3)

What’s in a name?

In our collections display, ‘Pictures of the Floating World: Japanese Ukiyo-e Prints’ we celebrate the wonderful collection of Japanese prints from the Edo period (1603-1868), the majority of which were given to York Art Gallery in 1954 by J.B. Morrell.

One of the challenges in researching these prints has been to establish or confirm the artist and date. The tradition in ukiyo-e of passing names down from father to son or teacher to student is fascinating yet occasionally confusing when trying to pin down an attribution.

Most ukiyo-e artists were apprenticed to a teacher, or master within a ‘school’. These were not art schools in the western sense, but a group of artists within a lineage with the most senior as head of the school. In the 19th century, the Utagawa school was extremely powerful and prolific. The lineage was so successful and flooded the market to such an extent, that it can be said to define the ukiyo-e genre in the Edo period. Over half of the ukiyo-e prints known today were produced by artists associated with the Utagawa school. Many of the artists in our exhibition carry the name ‘Utagawa’.

When a student was accepted into the school, they were able to take ‘Utagawa’ as part of their name. Once they achieved a certain level of success, they were also given an artist name (gō). This usually comprised the last character of their master’s. For example, the first part of Kunisada’s name came from the last part of his master’s – Toyokuni. This can often help us work out the lineage and relationship between artists: Those with ‘Kuni’ as part of their name, were likely to have been taught by Toyokuni. In the same way, Shigenobu was a student of Hiroshige, who was a student of Toyohiro. When a senior artist died, the next most senior artist would be able to adopt his name and those beneath him in the hierarchy would all move up a step.

To use Toyokuni as an example: His favourite student was Utagawa Kunisada. After Toyokuni died, Kunisada was able to adopt his name, so he then started to sign his works ‘Utagawa Toyokuni’. To avoid confusion, the master became referred to as Toyokuni I, and Kunisada became Toyokuni III (Toyokuni II was briefly used by Toyoshige, who was the son-in-law of Toyokuni I). In turn, Utagawa Kunimasa III (1823-80) was taught by Kunisada, so he was ‘upgraded’ to Kunisada II, and later became Toyokuni IV.

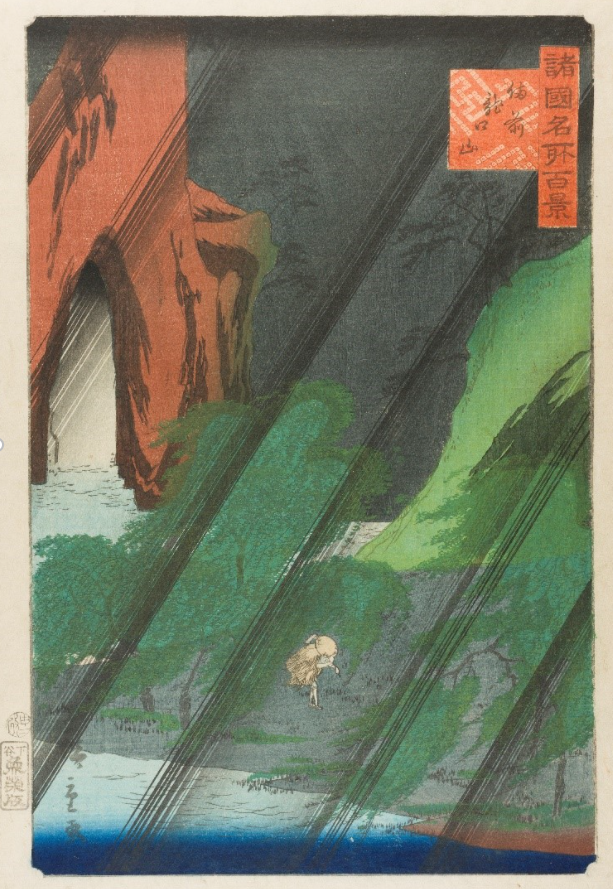

This means most artists signed their works by numerous different names in the course of their career. Katsushika Hokusai is known to have used over 30 different names at different points. In the course of my research I discovered that a print which was listed as by Hiroshige (1797-1858) (illustrated here), was in fact by Shigenobu (1826-1869), who was also known as Hiroshige II.

‘Tatsunokuchi Mountain in Bizen Province ‘The Dragon’s Mouth’’, from the series ‘One Hundred Famous Views in the Various Provinces’, 1860

As well as establishing the artist, signatures can help narrow down the date of the work. Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865) signed his designs in different ways and with different wording, sometimes interchangeably:

For this work by Kunisada (Toyokuni III) ‘Theatrical scene with Sawamura Sojuro as Saigio Hoshi and Arashi Kichisaburo as Zenshin Gompachi in a scene from a play’, there was no date listed.

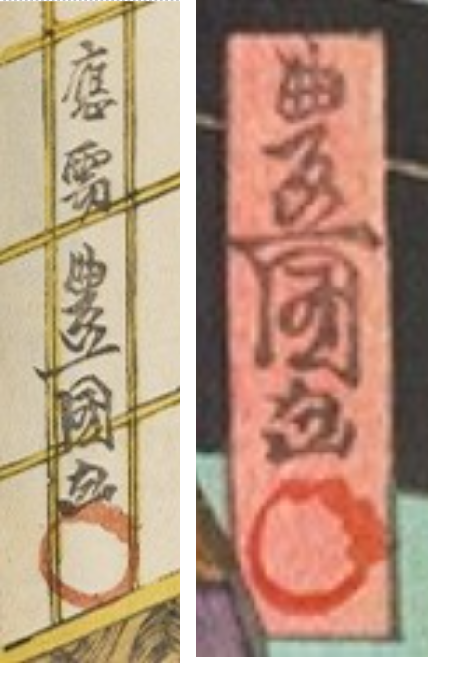

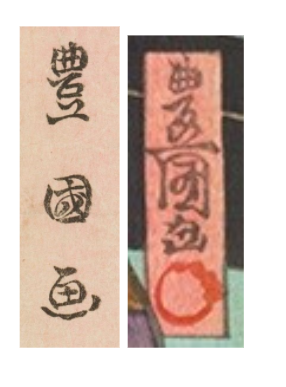

The left sheet in this diptych is signed ‘oju Toyokuni ga’, meaning ‘To satisfy the demand, drawn by Toyokuni’, and the right sheet is signed simply ‘Toyokuni ga’ (‘Drawn by Toyokuni’). It is known that Kunisada adopted the Toyokuni name in 1844, and in 1844/1845, he used the phrase ‘Kunisada aratame Toyokuni ga’ (or variations of this), which means ‘Drawn by Kunisada changing his name to Toyokuni’. So we can be sure that this print dates to some time after 1844.

Furthermore, the signature on almost all of the artist’s prints after about 1850 were enclosed in a decorative frame. As the signatures on this print are not enclosed, we can be fairly confident that it was not produced after 1850. This means we have a possible date range of 1845-1850.

The next clue lies in the actors’ names. Like artists, kabuki actors also inherited their kabuki names and were known by several different names over the course of their career. Sawamura Sojuro V (1802-1853) was no exception, and he carried the Sojuro name between 1844 and 1848. This almost exactly corresponds with the date range we have for the print. Combining both together gave us the current date range of the print – about 1845-1848.

There is, however, much scope for confusion and misattribution of artworks. The signatures on the Kunisada print (above) and this by Toyokuni I (below) both say ‘Toyokuni ga’, but they are by different artists. It is only when comparing both signatures side by side, that it is clear that they were not both produced by the same hand. We also have to take into account stylistic difference in the artworks themselves.

Research into these prints is ongoing and there is still much to discover. The final iteration of ‘Pictures of the Floating World: Japanese Ukiyo-e Prints’ is currently on display at York Art Gallery to enjoy until early November 2022.

Acknowledgement: The Kunisada Project Utagawa Kunisada (Toyokuni III) – Project and Kabuki 21 KABUKI (kabuki21.com) were invaluable resources in my research into the works discussed in this blog post.