Pictures of the Floating World: Displaying York Art Gallery’s Japanese Prints (Blog 2)

York Art Gallery houses an outstanding collection of over 1,100 paintings, around 14,000 works on paper and almost 120 sculptures, not to mention our Centre of Ceramic Art, which holds the largest collection of British Studio Ceramics. One of the many joys and privileges of being a curator, is delving into the stores and selecting works to share with our visitors. The Upper North Gallery on the first floor is a space where we shine a spotlight on and explore aspects of the collection that aren’t widely known about, or haven’t been seen for a long time, and it is here that our collections display ‘Pictures of the Floating World: Japanese Ukiyo-e Prints’ is located.

Although the prints have been in the collection since the 1950s, little to no research has been carried out since that time, so it has been my task (and pleasure) to delve a bit deeper. The main aim in my research has been to confirm artist attributions, dates, and to discover what I could about the subjects depicted in the prints, as well as their cultural context, their production, and of course, the lives of the artists. For the most part, I was able to corroborate the artists responsible, and I was also able to fill in some gaps such as dates and titles. In ukiyo-e, it can often be difficult to know which artist produced a print as most artists were known by several different names in their careers. More on that in another blogpost.

Recently, we were contacted by a visitor, Yiyi Chen, who kindly drew my attention to two prints that didn’t seem quite right: ones we had listed as by Suzuki Harunobu, and Katsushika Hokusai.

Suzuki Harunobu (c.1725-1770) is one of the most celebrated ukiyo-e artists and is credited with introducing and popularising ‘brocade’, or full colour prints (nishiki-e). Up until 1765, printed colour was limited to one or two tones, or alternatively more colours were applied by hand after printing. Harunobu’s first full colour prints employed multiple wood blocks to produce each vibrant image using up to 12 different wood blocks – one for each colour. This revolutionised the process, meaning colour could be produced more consistently and efficiently. These first complex colour designs produced around 1765 were privately commissioned calendar prints which were exchanged as gifts. The wealth of his patrons meant Harunobu was able to experiment with different woods and techniques. Publishing houses then saw their popularity and began using the technique for commercial prints.

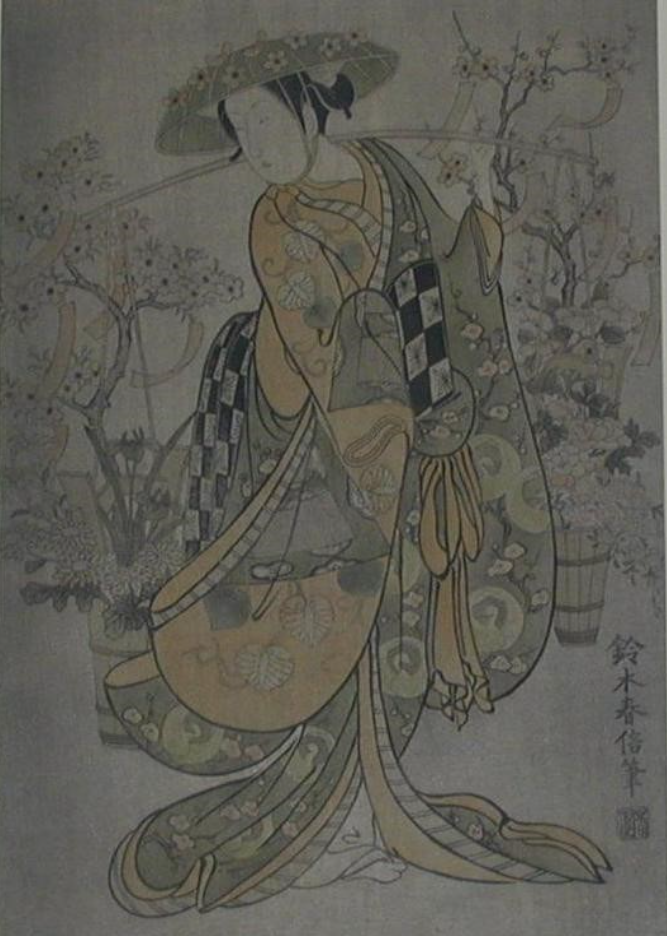

This print was listed as A Flower Seller, c.1751/1764 by Suzuki Harunobu. Yiyi noted that the paper didn’t look original. On comparing with another impression of a confirmed original online, we indeed found that the paper appears to be more modern and our print does not have the artist stamp in the lower left. As Harunobu was a well admired and respected ukiyo-e artist, his work was often copied or imitated, as is often the case with successful artists. Some further investigation is required, but ours is possibly a later strike from the same block, or a very close copy. This work is now recorded as after Suzuki Harunobu.

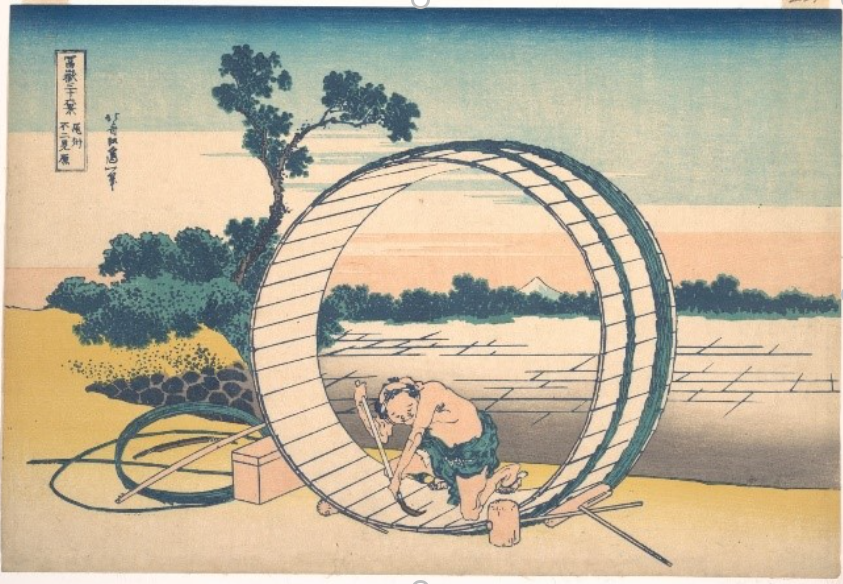

The second error Yiyi found relates to a print in our current hang – Fujimigahara in Owari Province, from the series ‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’ by Katsushika Hokusai (1760 – 1849) which shows a cooper making a barrel, with Mount Fuji visible in the distance. On the left is our image, and on the right is an original from the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York:

By Katsushika Hokusai – This file was donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See the Image and Data Resources Open Access Policy, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58783499

When comparing the works side by side, differences can be seen, such as in the lack of artist stamp in the upper left, and also in the quality of the drawing as well as differences in colour. We presented this work as by Katsushika Hokusai, yet we can now see that this is not the case. It seems likely that it was produced by a later artist as part of a group of works celebrating the great master. Again, we have now listed this work as after Katsushika Hokusai.

Although these are not quite the original objects that we initially believed them to be, these prints do still have their own value. They help us to tell the story of key ukiyo-e artists, and the esteem under which they were held – such that later artists studied, copied and celebrated their work. We are very grateful to Yiyi Chen, and indeed all our visitors who make contact with information about the artworks in our care.

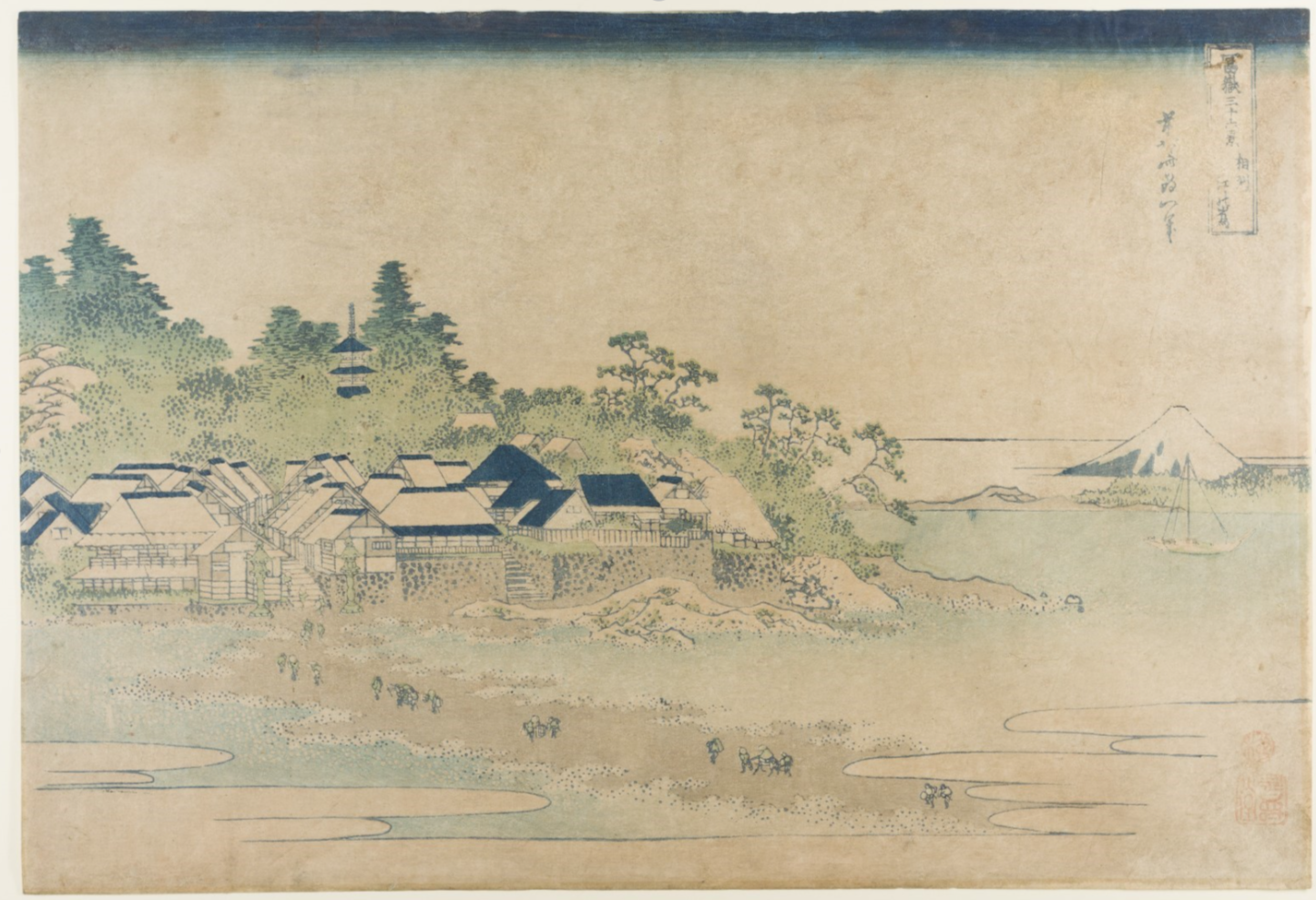

The Great Wave off Kanagawa by Hokusai, is perhaps the most famous Japanese artwork there is and the original design was produced as part of the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. Hokusai produced this series from about 1830 to 1832, when he was in his seventies and a hugely successful artist. It is considered to be his great masterpiece. Although we now know our impression of Fujimigahara is not an original, we do have another print from that same series which is currently on display – Enoshima in Sagami Province, (below) which shows worshippers approaching the temple at Enoshima island, and you can see both at York Art Gallery until 8th May.