Museums Displaying Disability

The difficulty with interpreting objects that are connected to disability in a museum space, is that they often, unintentionally, perpetuate the medicalisation of individuals rather than telling the lived experience of the people it connects to or resonates with. Many museums, including York Museums Trust are changing this narrative to give a true representation of people’s lives, and not only their disability. To do this, we move away from the object being the focus and towards the person.

For objects that were acquired without the personal experiences, museums can be creative with their responses by using them as prompts for discussion about the past or ways to talk about treatments and discrimination today.

In addition to this, people living with disabilities have a full life, and although they do face discrimination, it does not define their whole lives. Therefore, as with all marginalised and underrepresented groups, they should not be seen in museums by their protected characteristic but by their whole lived experience.

To start this off at York Museums Trust we have asked members of the York Disability Rights Forum to choose some objects in our collection and produce a response to them.

Elki Shaw

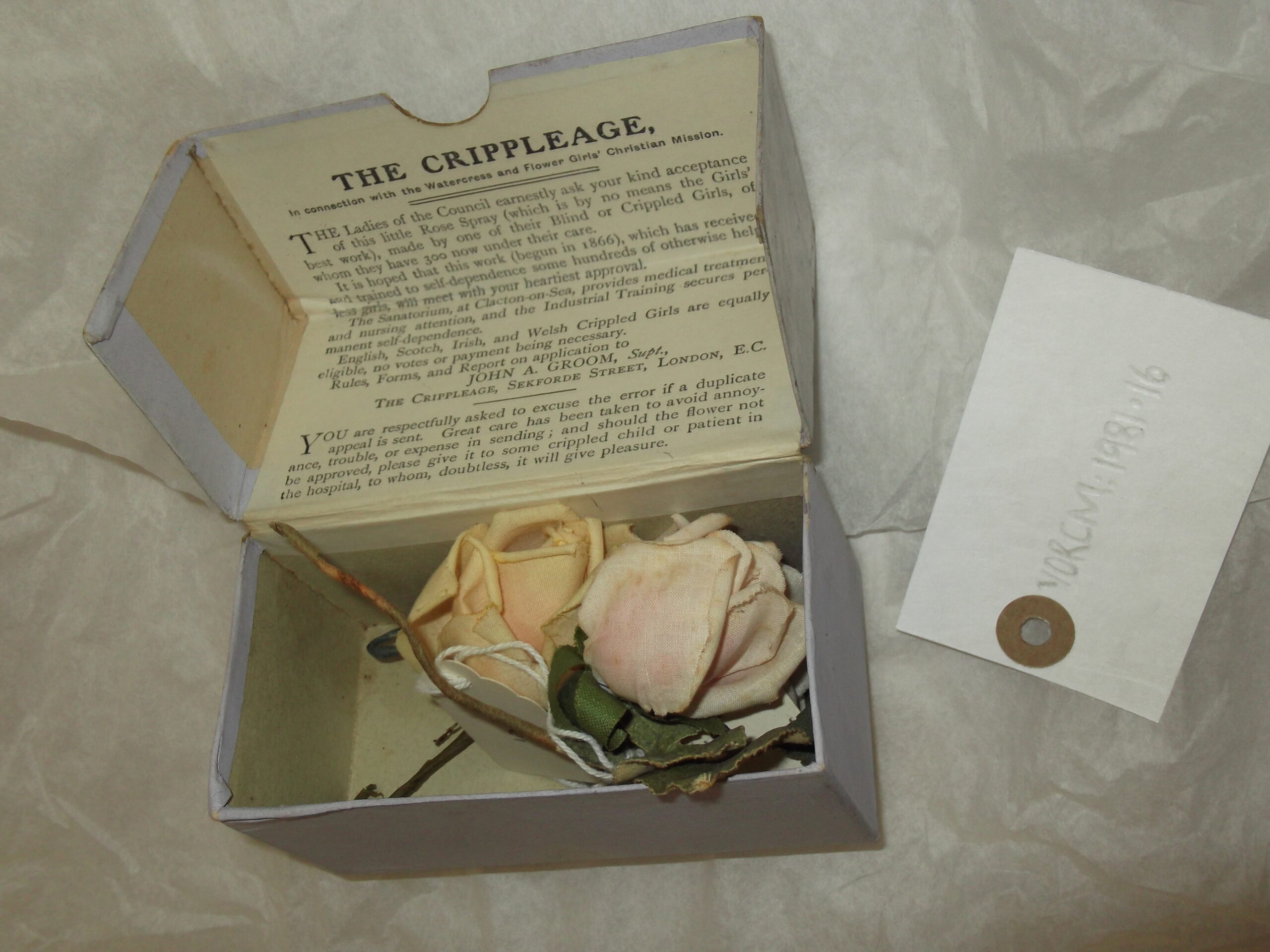

YORCM : 1981.16 The Crippleage Frabric Rose

I chose this one because I love the word cripple!

While I was growing up with a disability I was fortunately never subjected to the word cripple being used towards me as a slur or insult. The first time I came across it was when I was younger and my older brother, who had a Blue Badge, was driving us around. Upon parking the car he proclaimed with delight that we were using ‘cripple power’. I thought he was very cool. So my first introduction to the word cripple was one associated with a sense of pride and amusement, although it was clear from the way he said it that it wasn’t a word that belonged to the majority.

The word cripple has such power, but perhaps not in the same way it used to. Here it was clearly not meant to be a term of offence, the words ‘crippled girls’ are used freely throughout the message included with the rose spray as a casual and acceptable description of the condition of the young girls to which the item refers. However, referring to the girls in this way presumably elicited feelings of sadness and pity from the recipients of the roses. An effect that may or may not have been intentional.

Where the aim is to purposefully diminish, dismiss and ‘other’ someone, the word cripple used against a person has incredible power. It’s a power that has roots in the aforementioned casual and acceptable way it’s used to describe a complex and wide array of individuals. Applying a single label to a vast swathe of human beings who exist along a spectrum is, if nothing else, pretty lazy. Although some of the words that are now used to describe disabled people are more ‘acceptable’, the idea of disability still conjures up feelings of sadness and pity. And there still remains within society a level of laziness and reluctance to be uncomfortable which continues to result in disabled people being diminished, dismissed and ‘othered’.

These days when I see and hear the word cripple (sometimes ‘crip’) it’s regularly used in the same way that my brother said it. As a word of power, laced with pride in someone’s own identity. A word claimed and used by ‘cripples’ themselves, accompanied by bright and powerful imagery, not sad, mild, apologetic little boxes of flowers. A word that, for me at least, comes with a slight tinge of amusement at the discomfort it can cause people who have never experienced the delight of having a strong minority identity. Perhaps that is easy for me, having never been directly subjected to negative use of the term. It’s not my word, I didn’t reclaim it. But I’m so glad that my community did.

Helen Jones

YORK 2008 2412 – Victorian Invalid Carriage

Invalid.

In-valid.

In valid.

Not valid.

Not able to be accepted.

—-

“Aww isn’t she so cute…?”

No, I fume, I’m an adult.

“Does she take sugar in her tea?”

No, I fume, ask me.

The black pushchair

– three wheels and folding hood –

strip me of humanity

in the eyes of others

I am charity.

Marije Davidson

YORCM : AA9199 Image of students from York Deaf School on a trip to Boston Spa

I know nothing about these people apart from what the title tells me – that they are “York Deaf members visiting Boston Spa”. They would have been members of the York Deaf Society based at Number 61, Bootham (they’ve since moved to Huntington Road). Would they have been going to a reunion of St John’s Catholic School for the Deaf in Boston Spa? It was a school where deaf children were punished when they signed. Would the adults in this picture have refrained themselves from signing on the school grounds? I imagine that the driver and the man behind him were not deaf as they stare straight ahead and don’t look into the camera. The York Deaf Society would have been a place for deaf signers to be themselves, access information, and contribute to the community in a way that society often would not let them. Now we can’t come together like the people in the photo, in the Railway Institute or Huntington Road, but deaf signers are meeting virtually, locally, nationally, and internationally. A photo of these times would be a screenshot of a gallery of faces and hands.

Pain and Pride.

YORCM : AA10247 – Roger’s Vitalator Violet Ray High Frequency Electro-Medical Appliance

The Roger’s Vitalator was a cure all treatment device popular in the early 20th century. Using a high frequency violet ray this electrotherapy appliance would be waved over, or inserted into, the body to achieve, supposedly, a myriad of miraculous effects. Guaranteed success, the booklet states from hysteria, insomnia, nervousness, face ache, dizziness, obesity, asthma, acute rheumatism, congestion of the brain, epilepsy and many other aspect of debility.

The Roger’s Vitalator is an important ‘medical’ apparatus for us to reflect upon during disability history month. This is both to recognise the importance of scrutinising such devices for the way they reveal historical attitudes to impairments and disabled people, but also the cultural legacy that lingers on from such items in our attempts to beat the broken body and mind.

Treatment and aids, if they work, can be a blessing. They can free us from pain and provide useful ways to navigate and be in the world. They enable many of us to rehabilitate and participate in ways today unknown some 100 years ago. Yet an uncritical listening to the rhetoric of medical science and its transformative advancements might lead to a hearing of two things that have a deadly impact on disabled people.

The first is that human medical advancements can, if not now sometime in the future, beat any form of disease and then cheat death. And the second, which is implied by this is that the human body and mind has an optimal preferred state of being, and where possible this should be aspired to. Both of these are problematic.

The obsession with curing and treatments that seek to fix, have led many of us with diverse bodies and minds, and their everyday expressions, to be ostracised and othered. Disabled people throughout history have had much medical violence committed against them. Holes drilled in their heads, bones broken and re-set, braces, chemical coshes and segregated spaces. This is as our expressions leak upon established ideas of normality, disrupt orderly body conduct and challenge established ways we are expected to behave and participate in social spaces.

A counter to this is the social model of disability, articulated by disabled people during the 1970s. This asserts people are disabled by social barriers not their bodies, or minds, which are ultimately diverse. Barriers arise from the lack of access in the world, as well as the cultural values that promote and perpetuate a typical and optimal version of the human body, mind and conduct.

Though, it is not straight forward to apply the social model to the experience of pain. Pain is a very human and personal experience, and one that often requires intervention. But our reactions to it can be influenced by cultural values that favour optimal versions of the human body. Pain is not necessarily a social barrier, but the way we react to it, are supported with it and enabled to participate in society as we experience it, can indeed be so.

Yet pain is something we must explicitly acknowledge, and perhaps be proud of as it reveals us as feeling human beings. It is an integral aspect of being in the world, and a significant feature of the authentic, not the optimal body and mind. All of us will indeed experience some form or pain, some of us unbearably, some of us consistently. We should embrace this reality of pain while we look to achieve relief from it. This should be authentic and in such a way that rejects ideas of an optimal or normal way of being, but rather one that draws on the full range of beautiful and diverse body and minds that make up the world.

Stephen Lee Hodgkins – Proudly neurodiverse chronic doodler and printmaker interested in text, peoples voices and their experiences of local places and community spaces.

Tweet – @HodgkinsSL

Insta – stephen_lee_hodgkins

Nov 2020.