Maud Webster’s Sampler

Today, we would like to introduce you to a hidden gem from York Castle Museum’s collections: a sewing sampler made by a little girl in York 130 years ago. In February 2025, it went on display for the first time, as part of the York Makers section of the redisplayed Fashion Gallery.

Sewing a sampler was a standard part of girls’ education well into the 20th century. Back in the 17th century, when York Castle Museum’s oldest sampler was made, samplers of decorative needlework were usually made at home by girls from wealthy families. Evidence suggests these were partly a training activity and partly a kind of stitch guide, helping the stitcher to remember each technique.

Fast forward to the end of the 19th century, and most girls still sewed samplers. In the 1890s, school prepared working class girls for employment in domestic service and for life as a housewife. Learning to sew the alphabet and numbers meant that she could accurately label her family’s or her employer’s clothing, bedlinen and other household textiles, an essential task that helped households keep track of everything they owned. But sewing a sampler was more than that: it allowed girls to show off the skills they had learnt and maybe also to exercise a bit of creativity.

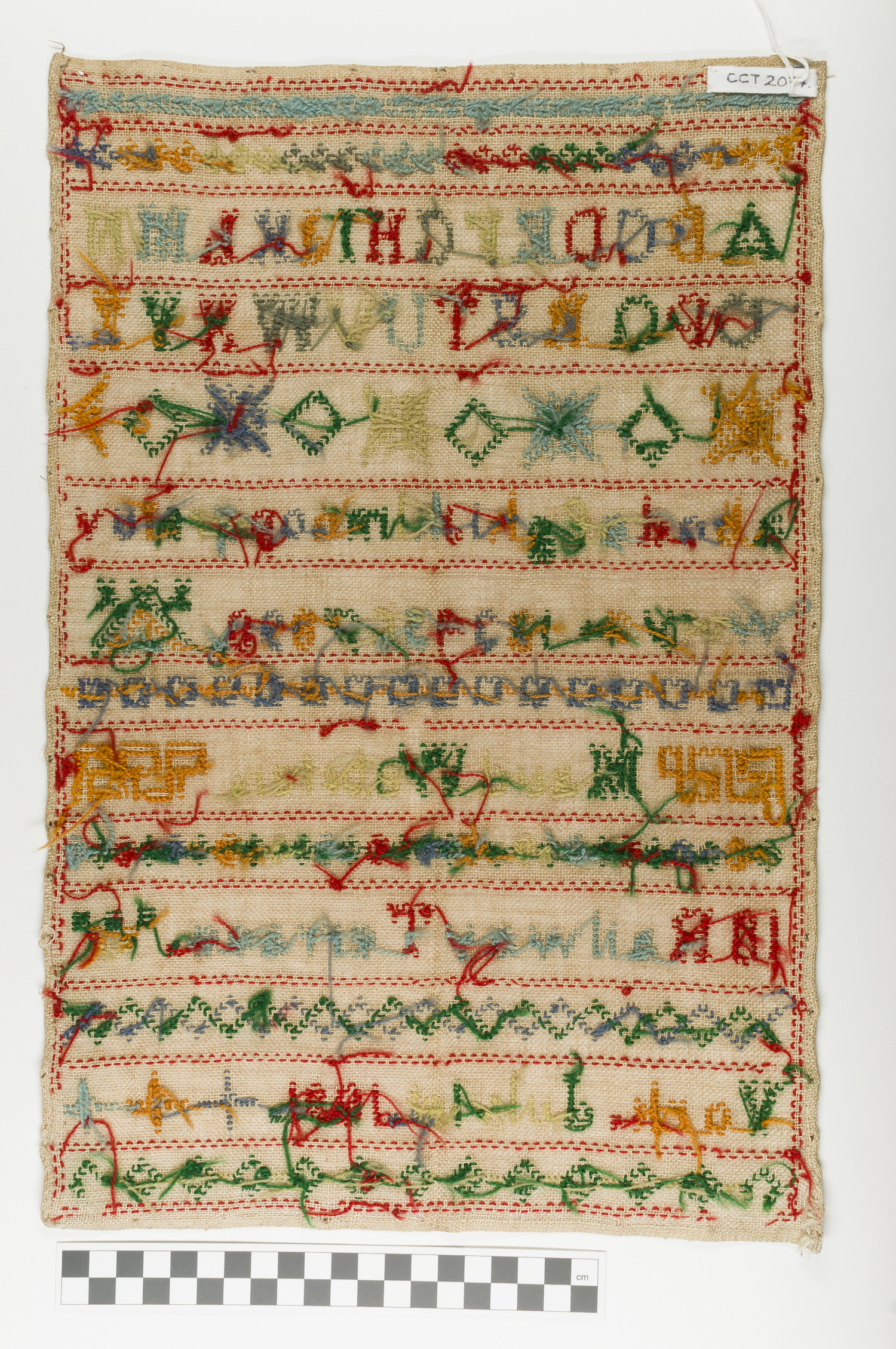

This sampler was made in 1891 by Maud Webster who lived at 10 Railway Terrace, York. She sewed her name and address, along with an alphabet, numbers and a decorative border.

Maud was 9 years old, and it’s likely she made the sampler at school. We believe she went to St Paul’s School in Holgate, which still operates as a primary school today. Maud was among the first generation of children to have free compulsory primary education in England. From 1880 onwards, by law all children had to attend school between the ages of 5 and 10.

Her experience would have been very different from that of her parents’ generation. Her father, a butcher called Thomas Webster, and her mother Alice were raised at a time when working class children might go to school if their parents could afford the fees, and if they could afford for their children not to be at work. Most children left school very early. Some free schools did exist, but these were not available to everyone.

The 19th century saw massive changes in attitudes towards children and childhood. At the beginning of the century, many children worked. Their jobs were often dangerous and their shifts were very long. Many pieces of legislation were put in place by the government aimed at getting young children out of work and into school. Most effective were the Factory Act of 1833 which limited children’s working hours, and the 1880 Education Act which made it a legal requirement for all children in the country to have a primary education.

When she left school, Maud did not go into employment and she didn’t get married. Instead, she lived with her parents until her father passed away, then she went to live with one of her two brothers and his family. Maud lived with them for the rest of her brother’s life. We can’t assume that this is a sad story – we don’t know what Maud herself thought, she might have been very happy. We do know that she didn’t have her own income though, because after her brother’s death she moved into St Thomas’s Hospital, an almshouse on Nunnery Lane, York. St Thomas’ Hospital provided a home, food and other necessities for a small number of elderly people who had no other support. The building where Maud spent her final years still exists.

St Thomas’ Hospital, Nunnery Lane, York by Malcolmxl5, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

In 1949, a year before her death, Maud donated her sampler to the museum. If she sent a letter with it, this was not preserved, but the sampler itself holds a hint about Maud’s feelings. Look along the edges, and you might spot some holes showing where small tacks used to be. This shows us that the sampler was considered special enough to be mounted in a frame.

We only know about Maud because of research undertaken by York Makers Volunteer Francesca Infantino. You can read more about Francesca’s experiences in her blog about Maud.