Bringing Tempest Anderson to Life – by Rebecca Hall, Science Team Volunteer

York Museums Trust volunteers Rebecca Hall and Barbara Boize have been working with our digitisation officer Chris Streek to digitise the vast collection of Tempest Anderson’s photographic slides. In this blog entry, Rebecca gives an overview of this painstaking process.

Tempest Anderson was an amateur volcanologist and photographer from York who travelled across the world documenting volcanic eruptions and the people that they affected. When he died in 1913 he donated approximately 5000 photographic slides to the Yorkshire Museum.

The Museum receives requests regularly to view images from the collection; because of this, it has been decided that the entire collection should be digitised to make it available for the public and the scientific community to use and appreciate.

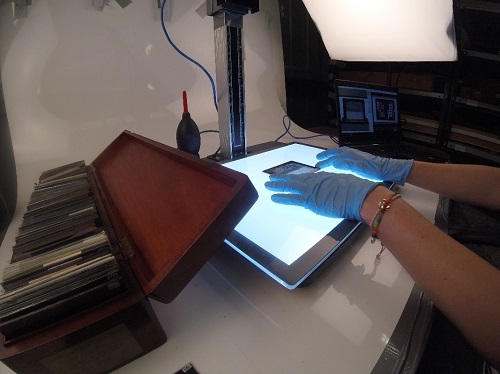

Before the slides can be imaged they need to be carefully cleaned. They are packed tightly in boxes made of either cardboard or mahogany and dust and dirt has transferred to their surfaces over time. The negatives are usually found in protective archival sleeves but still need to be removed and cleaned of any deposits.

The glass is wiped carefully with cotton wool dampened with deionised water and then dried with a lint free cloth to remove residual fibres. If possible, the back of the slide is also cleaned so as not to transfer dirt between slides in the box.

A light box is used to make viewing the images on the slides much easier.

The slides are imaged whole to capture the object in its entirety and log its current condition, along with any information that is apparent on each slide frame. The set up uses even lighting and ensures that there are no shadows.

It is important here to make sure that the object is in the correct orientation, otherwise it increases the workload at the processing stage. A sufficient gap is left around all four edges of the slides to allow for slight adjustments to be made later. The light box has to be kept free of any residues that would otherwise show up on the final image.

It is helpful to straighten the slides at this point to reduce processing later on.

Each image is given its own unique reference number for use both during processing and once they become available to the public. Any slides without a physical number are logged using an in-house error reporting protocol and renumbered if necessary.

Not all slides have retained their numbering. These ones are logged and the identity established using the Museum’s catalogue system.

Image processing is then done by the York Museums Trust digitisation team. They colour-correct, crop and straighten the images and any small blemishes can also be removed at this point on a derivative version.

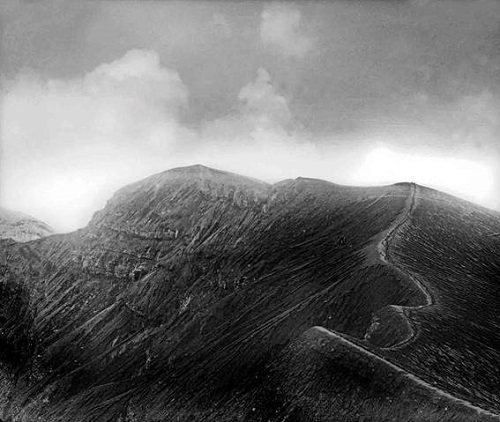

The original image is then saved as a master file and the derivative processed further by converting to black and white, and any damage or blemishes removed to produce a clean version.

An example image before (top) and after (bottom) processing by Chris Streek. Blemishes that can be removed at this stage are highlighted by the red arrows. (YORYM : TA3-001)

Once all this has taken place, the images can then be digitally archived. Similar protocols are being adopted to digitise other important objects at the Museum, including interesting coin collections.

It is a great way to engage, appeal to and educate a whole new audience and provides a large amount of new information to interested scientists.

In her next blog post, Rebecca will be highlighting a couple of her favourite images from the collection. Keep visiting the York Museums Trust website for more behind the scenes updates.